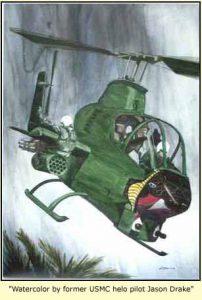

The Noble Warrior: Rescue at Hill 845|by Lieutenant Colonel Gregory J. Johnson, USMC (Ret)

Glancing around at the clutter in my attic recently, I decided it was time to sort through some of the unpacked boxes associated with my military retirement and move to Pennsylvania. A fond smile crossed my face as I gingerly pulled out aging flight logbooks. As I randomly scanned the yellowing pages, I was surprised by the vivid and detailed recall the numerous sorties inscribed on those pages evoked. Aviation seems to have that effect on the mind.|by LieutenantColonel Gregory J. Johnson, USMC (Ret)

Glancing around at the clutter in my attic recently, I decided it was time to sort through some of the unpacked boxes associated with my military retirement and move to Pennsylvania. A fond smile crossed my face as I gingerly pulled out aging flight logbooks. As I randomly scanned the yellowing pages, I was surprised by the vivid and detailed recall the numerous sorties inscribed on those pages evoked. Aviation seems to have that effect on the mind.

Locked in a trance with my memories, it was the flutter of a small newspaper clipping surrendering to gravity, as it fell from between the pages, that snapped the spell of the moment and brought me back to reality. The clipping was a one-line notice from the Navy Times announcing the death of my friend, David Cummings, during 1988. When I first cut out the obituary notice and tucked it away in my logbook, I mentally promised myself that one day I would tell the story of his heroics–in another place and time…

(Vietnam 1969)

It was December. Reconnaissance elements from a battalion-size Viet Cong force probed the hasty defensive perimeter set up by a remote Marine observation team atop Hill 845. From afar, an OV-10 “Bronco” aircraft, responding to an urgent call from the outpost for close air support, swept in low from the south. The confines of adjacent mountain ridges, coupled with a rapidly deteriorating cloud base, made the pending interdiction strike especially hazardous. Monsoon season was well underway and, like the distant thunder, the drone of the Bronco’s propellers reverberated off the trees and mountain sides, striking fear in the guerrillas (as wounded VC prisoners would later relate) while providing some semblance of comfort to the beleaguered Marines.

The Bronco pilot and his rear seat aerial observer seemed oblivious to the danger. Directed to the attack by a ground-based forward air controller (FAC), the Bronco pilot focused his attack on a shallow ravine leading into the outpost encampment. Squeezing off two Zuni rockets, he visually tracked the missiles (with a little body language) to the ravine where they exploded in a fury of smoke and fire.

The pilot immediately banked his aircraft sharp to the left to avoid flying debris. Quickly leveling his wings, he simultaneously pulled back hard on the control stick. His Bronco was now pointed straight up. Bleeding off airspeed for rapid altitude gain in an exchange of energy, the Bronco masked itself in the clouds to escape retaliatory ground fire and also to avoid collision with the mountains. In a matter of seconds, the aircraft punched through the cloud overcast. He leveled off the aircraft, adjusted the throttle, and waited for a radio call to announce the results of his attack. The FAC reported that the attack was successful. Further probing by the enemy had ceased. For the time being a second suppression attack would not be required.

During the siege on the outpost, however, the FAC reported a young Marine had tripped off an enemy booby trap and was seriously injured. Bleeding profusely, he was going into shock. The Bronco pilot was asked to relay a call for an immediate medical evacuation.

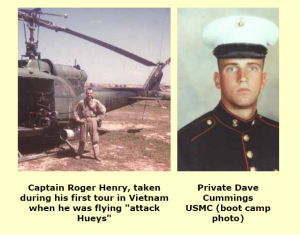

Meanwhile, at Landing Zone Baldy, Cobra pilot First Lieutenant David Cummings and his aircraft commander, Captain Roger Henry, were standing by on routine medevac escort alert in their AH-1G helicopter gunship. The rear cockpit seat of the Cobra, normally flown by the pilot in command, would today be flown by the copilot, Lieutenant Cummings, as part of his aircraft commander check ride. When the call came to escort medevac helicopters, the pilots launched with another Cobra to marry up with two CH-46 Sea Knight transport helicopters as part of a constituted medevac (medical evacuation) package. After a smooth join up, the flight headed 40 miles southwest of Da Nang into the Que Son Mountains in Quang Nam Province where they rendezvoused with the Bronco for a mission brief.

Weather at Hill 845 had deteriorated badly. Rain and lowering cloud bases made it virtually impossible for the large Sea Knights to get into the area for the pickup. Despite persistent maneuvering, the rescue flight finally retired to the edge of the weather mass where they loitered to wait for another opportunity to come in and pick up the wounded Marine.

After obtaining approval from the medevac mission commander, the agile Cobra flown by Captain Henry and Lieutenant Cummings, proceeded in to scout the landing zone in order to facilitate a more expeditious evacuation. The worsening weather, however, prompted Captain Henry, positioned in the higher visibility front gunner’s seat, to assume control of the aircraft’s more difficult-to-use side console forward cockpit flight controls. Visibility was now practically zero.

In those days, there was a variation of a popular song theme that “only mad dogs and Englishmen ventured into noonday monsoons!” Undaunted, Captain Henry and Lieutenant Cummings pressed on despite harrowing weather conditions. The two Marines worked their Cobra up the mountain-side amidst severe turbulence generated up and down gnarled mountain slopes. Scraping tree tops at airspeeds that often dipped below 30 knots, or required holding in perilous zero-visibility hovers, the flyers anxiously waited for a call from the outpost giving them either a visual or sound cue that they were above the elusive, ill-defined landing zone. After three hours and five different attempts (with refueling runs interjected in-between), the aviators finally found their mark.

Sporadic radio reports confirmed to Captain Henry and Lieutenant Cummings their worst fear that the injured Marine was succumbing to his wounds. Guiding the Cobra down through tall trees, Captain Henry landed the aircraft on the edge of a bomb crater in a skillful display of airmanship. The helicopter settled to the ground amid swirling debris. The tightness of the landing zone was such that only the front half of the aircraft’s skids rested on the rocky outer lip of the bomb crater. While the Cobra loitered in this precarious teeter-totter position, Lieutenant Cummings climbed out of the aircraft to investigate the situation.

Infantry Lieutenant Dave Cummings in Vietnam Dave Cummings pauses for photo while refueling and rearming during missions in Vietnam

Torn and bloody, the wounded Marine was drifting in and out of shock. Having served a previous tour in Vietnam as an infantry officer, Lieutenant Cummings was intimately familiar with the situation now confronting him. He had seen the haunting lurk of death in young men’s eyes enough times before to know that it was time to get this Marine out immediately. Death, Lieutenant Cummings promised himself, would not visit this Marine today if he had anything to say in the matter.

With the situation assessed, Lieutenant Cummings ordered the casualty lifted into the Cobra. Strapping the semiconscious Marine into his rear cockpit seat, Lieutenant Cummings fastened the canopy shut. As “mud Marines” looked on curiously, Lieutenant Cummings climbed atop the starboard stubwing rocket pod. Straddling the pod and facing aft, Cummings banged his fist on the wing to get Captain Henry’s attention before giving him a thumbs up. With a grim smile, Captain Henry nodded and took off. The cloud base, by now, was less than 100 feet above the outpost.

As the Cobra lifted away, the radio airways snapped to life as radio operators in the vicinity broadcast descriptions of the incredible scene they were witnessing. Atop the rocket pod, Lieutenant Cummings flashed a “V” for victory to those remaining in the zone as the Cobra vanished dramatically into the blanket overcast. It was the ultimate stage exit. Marines on the ground stood and cheered. Morale soared.

Leveling off in a cloud mass at 4,000 feet, Captain Henry accelerated the Cobra to 100 knots in order to improve maneuverability. Once stabilized, he glanced over his shoulder to check on the outrider. Lieutenant Cummings flashed him back a sheepish grin. Biting rain, extreme cold at altitude, and the deafening shrill and shuffle-vibration of engines and rotors all mixed to fill his senses. He could hold on only by squeezing his thighs tightly against the rocket pod wing mount. To exacerbate matters, the wind grabbed at the back of Cummings’ helmet flexing it forward thereby causing the chin strap to choke him. And all the while howling winds taunted him. But at their loudest, Cummings merely glanced at the wounded Marine, and howled back.

The Bronco pilot, still orbiting on patrol, began his return to home base as fuel began to run low. En route, he happened to catch a chance glimpse of the Cobra darting in and out of the clouds in its tenuous race against time. Zooming down for a closer look he was unprepared for the spectacle of Lieutenant Cummings, hanging outside the aircraft, and the bleeding, semiconscious Marine within. In mild disbelief, the Bronco pilot pulled up wide abeam the Cobra, gave a thumbs up and departed. “What a crazy war!” Herbert quipped to his observer while still shaking his head in disbelief. But in his heart, he knew this was the way of the warriors!

After the twenty-five minute flight through turbulent weather, the gunship descended through the clouds and broke into relatively clear sky at 1,200 feet over a land navigation point called Spider Lake. The Cobra now headed towards a medical facility. Thoroughly exhausted from the strain of the mission, Captain Henry was having trouble discerning the exact location of the medical site when he sensed a series of thumps coming from the starboard wing. Glancing to his right he saw Lieutenant Cummings, much like a prize-winning bird dog, with locked pointed finger directing his attention to their destination below.

After landing, the wounded Marine was whisked into a medical triage for stabilization while Navy Corpsmen, who thought they had seen everything, helped Cummings “defrost” himself off the rocket pod. A short time later, a CH-46 Sea Knight arrived to fly the wounded Marine to Marble Mountain for emergency surgery. Sprinting along through the sky as combat escort with the Sea Knight, to the more sophisticated “in-country” medical facility, were Cummings and Henry. The two, weary from fatigue, were nevertheless vested in their interest to culminate the safe arrival of the wounded Marine. (The young Marine survived, married, and was last known to be living in Texas.)

Despite the long day and fatiguing limits they had endured, Captain Henry continued the training portion of Lieutenant Cummings’ check ride on the way back to home base. Oddly enough, among senior aviators “in-country,” there was talk of censure and a court-martial for the outrider affair. The act had overtones, in their opinion, of grandstanding regardless of the fact that the young Marine would have died had he not received medical attention as soon as he did. However, when Henry and Cummings were both personally invited by the Commanding General of the First Marine Division to dine as special guests in his quarters, the issue of court-martial was moot and dead on arrival. For their actions, Captain Henry and First Lieutenant Cummings were each awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. Years later when asked about the dinning experience with the Commanding General, both pilots readily admit they thought they had a great time. Libations, it appears, were liberally dispensed. And it was reported to the two aviators that they were both transported horizontally into their hooches and gently tucked in their racks by the grunts!

(Prologue)

When Dave Cummings died unexpectedly in 1988, there were the normal expressions of loss, especially for one so young. But none who first attended his lifeless body, and only a few who were present at his hometown funeral, fully realized the magnitude of his life or the legacy he had left with the Corps.

A native of Woburn, Massachusetts, Cummings enlisted in the Marine Corps during September of 1966. Upon completion of recruit training, he attended Officer Candidate School and The Basic School at Quantico, Virginia. Cummings served several months as an infantry platoon leader with the Second Battalion, First Marine Division in Vietnam. After being seriously wounded in a fire fight with Viet Cong forces, he was evacuated to the States. Cummings had always wanted to fly so it was a thrill, following recuperation, when he was selected for flight training. Earning his “Wings of Gold,” Dave Cummings returned to Vietnam during September 1969 to start his combat flying career.

Nineteen years later, Lieutenant Colonel Dave Cummings, en route to attend a special military course in Albany, Georgia, stopped in Atlanta for the night. After a routine workout, he returned to his hotel room where he suffered an apparent heart attack and died. He was 42.

Although Dave Cummings’ life spanned a relatively short period of time, he managed to walk a worthy journey. Among his personal military awards were four Distinguished Flying Crosses, four single mission Air Medals, the Bronze Star with combat “V”, and a Purple Heart.

In this day and age when the term hero is used so loosely, it is comforting that I can say I actually have known some true ones in my lifetime. Dave Cummings was a man who set the example. He was a guy who displayed courage that all of us who knew him hoped we could muster if the call came. Dave Cummings was a special piece of the Corps’ past, a large measure of its tradition, and maybe, more importantly, a sizeable chunk of its soul. He will not be easily forgotten. Semper Fi, Dave.